Kampala, 23rd June, 2017 – Gold exports reached $340 million in 2016, according to official figures, up from $237,000 in 2014. New mining sites are opening across the country, creating jobs for thousands of people.

But a new report from environmental NGO Global Witness claims there is a dark side to the boom, that the mineral sector is fueling corruption, conflict, human rights abuses, and environmental damage.

The 18-month investigation “Uganda Undermined ‘’ draws on interviews with miners, company executives, government officials, and industry experts to paint a stark picture of the sector.

“Our investigations show that Uganda’s mining sector is characterized by corruption, mismanagement and high level political influence,” says George Boden, Uganda campaign leader at Global Witness. “Impunity is endemic and attempts at reform have all failed in the face of entrenched interests.”

The Kilembe mine on the border of protected site Rwenzori Mountains National Park.

License to shill?

The report alleges systemic corruption at the Directorate of Geological Survey and Mines (DGSM), the government body that awards mining licenses, operating under the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development (MEMD).

“Corruption has become institutionalized at the Directorate,” the report claims. “It is almost impossible to obtain licenses from the DGSM without making payments to certain DGSM mining officials…(and) Directorate officials are expected to provide preferential treatment to companies favored by the political elite.”

Global Witness cites cases of senior DGSM staff simultaneously serving as directors at companies applying for licenses, in apparent conflicts of interest.

The NGO also reports complaints from staff who say their decisions were overridden in favor of investors with political connections.

A spokesperson for the MEMD acknowledged problems with the licensing process and told CNN it is under review.

“Some of the issues raised by the report such as licensing are bought about because of weaknesses and loopholes in mining policy and laws,” the spokesman said. “The ministry is currently reviewing these policies and we hope that some of these challenges will be cleaned up.”

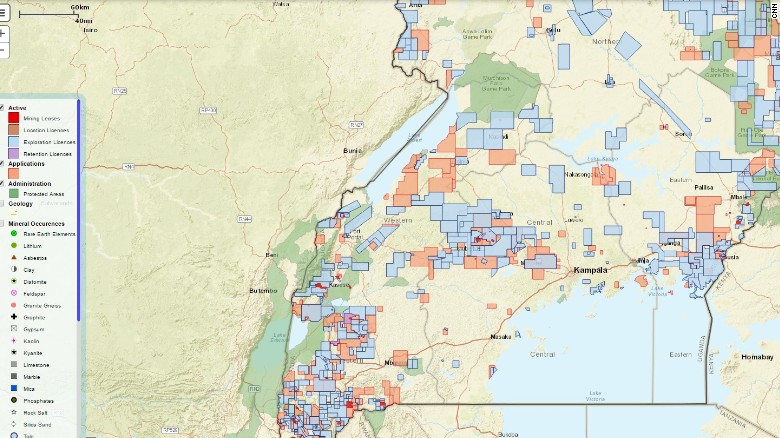

Uganda’s mining cadaster shows licenses granted in protected sites.

Collateral damage

The report also highlights environmental damage caused by the lax licensing regime.

The Ugandan government’s mining cadaster shows that licenses have been issued inside many of the country’s protected sites, including the UNESCO-certified Rwenzori and Bwindi national parks. The latter is home to nearly half of the world’s population of endangered mountain gorillas.

The report quotes one license holder, MP Elizabeth Karungi, claiming to have secured a permit inside Bwindi through personal connections to another government official.

When contacted by CNN, Karungi confirmed receipt of the license, but said that the site had not been excavated.

Such incursions are “dangerous for conservation efforts” said Dan Kaweesi of the Uganda National Commission for UNESCO.

“We risk losing the world heritage site status for the two sites involved,” he added. “This is bad news for heritage preservation.”

The UNESCO-certified Bwindi National Park contains the world’s largest population of endangered mountain gorillas.

Community impact

Global Witness says that poor regulation and oversight are also enabling human rights abuses.

The report documents cases of child labor on mining sites and dangerous conditions such as exposure to toxic chemicals.

Such accounts are corroborated by local campaigners.

“Some mining companies offer jobs (to local communities) as casual laborers but this work is under harsh conditions with limited or no safety and protective gear,” says James Muhindo, a lawyer and human rights advocate at the Ugandan NGO Global Rights Alert.

Muhindo further claims that communities, such as nomadic herdsman in Northeast Uganda, who are surrounded by major gold and marble excavations, are being displaced by mining companies.

“Their way of life has been affected by the mining companies’ private and exclusive ownership of large chunks of land,” he says. “Previously (the land) was communally-owned with free access to pastures for the entire community.”

The report alleges child labor is rife in Uganda’s mining sector.

Lack of transparency

Communities struggle to claim compensation for the land, says Muhindo.

One major obstacle is that companies rarely declare their profits, making it difficult for landowners to calculate what they are due, and for local authorities to claim tax.

The problem is national as well as local. Global Witness believes Uganda is losing out on millions of dollars of tax revenue.

The report highlights the case of a gold refinery with connections to Salim Saleh, brother of Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, which allegedly received lucrative tax exemptions.

According to the report, the lack of transparency may also conceal smuggling. Uganda is a signatory to the 2010 Lusaka Declaration on controlling conflict minerals agreed by the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR). But “Uganda: Undermined” cites gold dealers who say they are handling minerals from South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

A spokesman for the ICGLR told CNN the group had heard “many allegations from different sources” on the smuggling of conflict minerals through Uganda, and urged the government to apply its regional certification mechanism with neighbor states to toughen diligence.

A gold mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Global Witness believe Uganda’s gold rush may be fueled by minerals from conflict areas.

Reform prospects

Tighter control of conflict minerals is just one area of reform being proposed for Uganda’s mining sector.

The World Bank is working with the Ugandan government on a new, wide-ranging mining bill that aims to tackle entrenched problems.

“The new legislation will include background checks for licensees (and) the sector must be better regulated so the government can easily collect taxes,” a MEMD spokesman said. “The government is losing money because of a weak mining policy, and the laws will be changed.”

Don Bwesigwe Binyina, executive director of the Africa Centre for Energy and Mineral Policy, is also working on the bill. He hopes for a profound cultural shift.

“Corruption is just one problem,” says Binyina. “Institutional weakness is another challenge…the sector has limited human resources, for years it has been receiving reduced budgetary allocations.”

The director points to Uganda’s petroleum sector that is “one of the best trained on the continent” as a model of what could be achieved. He believes a focus on building skills and capacity as well as governance could make the sector a vehicle for change that could transform life prospects for much of Uganda’s low income workforce.

Should such plans come to fruition, Uganda’s gold could yet be, for many, more of a blessing than a curse.

Credibility: http://edition.cnn.com